Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

‘Building business models that merely pursue profits almost pale as a hedonistic or pecuniary quest aside the grand challenge of building business models that matter.’

– Alex Osterwalder

Most business surveys will reveal that having a good business model has become more important than having a new product or service.1 According to most textbooks, designing a business model is easy. One should figure out what value the firm can bring to which customer segments, find the best way of doing so, and it should work for both the customer and the business. The real world, however, is not one where clients, managers, suppliers, employees, and the society magically want the same.

This thesis explores the decisions top-managers make about their firms’ business models in the presence of strategic demands of a particular kind - paradoxes. Strategic paradoxes denote competing, conflicting, yet interrelated strategic goals, which cause tensions as a result of seemingly irreconcilable requirements and persist over time (Smith and Lewis 2011; Lewis and Smith 2014; Jarzabkowski, Le, and Van de Ven 2013). Most commonly, strategic paradoxes are pairs of goals, which appear as opposites but are both needed. Think of learning and performing, long-term and short-term planning, exploring and exploiting. While I study how the conflict between creativity and commercialization is navigated in creative service firms2, the work presented in this thesis is driven by a broader question, namely - how can firms use business model design to make conflicting, yet interdependent strategies work? I strongly believe this question is relevant beyond the studied field, as incorporating beyond-profit considerations, mostly social and environmental, in enterprise design is (hopefully) on its way of becoming the norm. At a personal level, it is driven by a more mundane question - when presented with seemingly impossible choices, how do we proceed in the most successful way? How do we as entrepreneurs and decision-makers kill two birds with one stone?

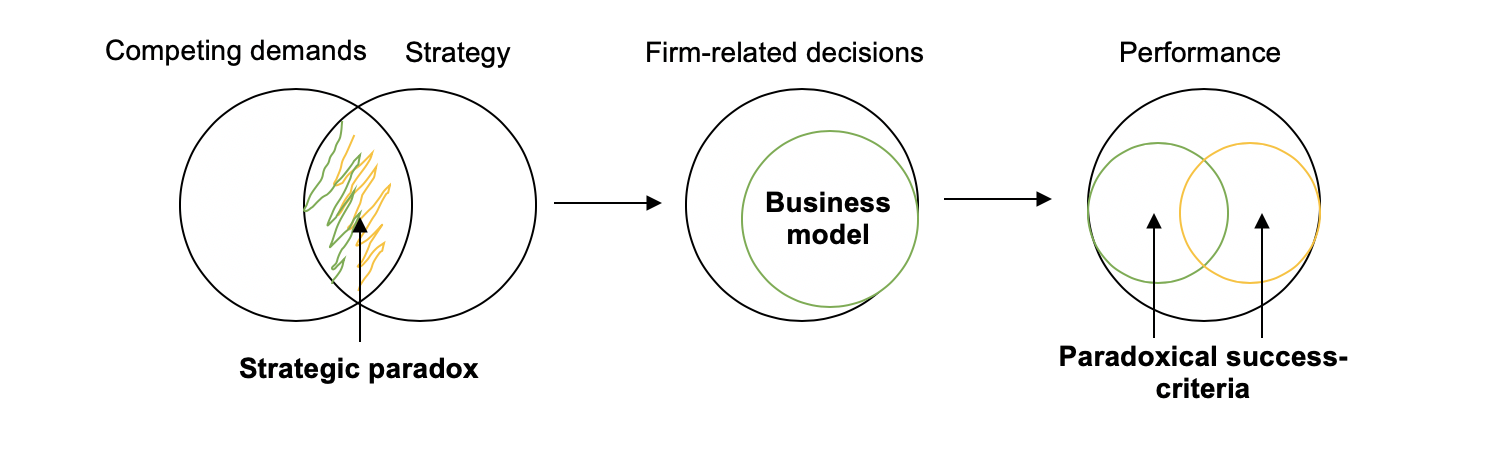

Business models were chosen as the focus of investigation for they are increasingly recognized among the most important sets of strategic decisions that firms can make, determining largely the value that firm creates (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2011). This is also how I understand business models in this thesis - as a set of decisions made about the product(s) and/or service(s) to deliver, target customers, as well as the appropriate value creation and capture mechanisms to link the two (Smith, Gonin, and Besharov 2013). To explore the process and content of business model design for strategic paradoxes thus means to explore the specific decisions and the process behind them. I use paradox theory as a conceptual lens for framing competing demands, and creative industries as an exemplary paradoxical setting. The general model is presented in Figure 1.1, and the concepts of focus on are marked in bold.

Figure 1.1: Conceptual relationships between the theoretical domains used.

These relationships are investigated through one conceptual and three empirical studies, each using different methods. In the consequent sections I explain the main theoretical and methodic assumptions this thesis relies on. I address three questions in particular - 1) Why paradoxes?; 2) Why business models?; and 3) How should we conceptualize organizations in order to study the relationship between the two? The question “Why creative industries?” will be tackled in-depth in the next chapter.

1.1 Encountering and studying paradoxes: Why?

How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress. (Niels Bohr, 1885 - 1962)

Uninventively, this is the most common quote about paradoxes one would find in an online search. It comes, however, from a field very distant to that of organization studies - quantum physics. I hope you will forgive the short detour and take this leap with me.

This quote was part of Niels Bohr’s response to Einstein’s famous thought experiment ‘Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical reality Be Considered Complete?’ (Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen 1935). In this article, Einstein put forward what he considered a fundamental flaw in the quantum mechanics. This at that time very new field of physics posited that a measurement performed on one particle from an interacting pair would affect the state of the other particle in the same way, no matter what the distance between them. According to Einstein, this was untenable, as it would have meant that information is transmitted faster than the speed of light, thereby defying the Theory of Relativity. In short - the main premise of the new-born quantum mechanics field seemed counterintuitive, and hence could not be true. However, this is, in fact, now known as the EPR paradox, and is one of the best-known examples illustrating the concept of quantum entanglement. But how can we link quantum mechanics with the study of organizational paradoxes? Besides being a beautiful quote about the opportunities paradoxical encounters can offer, the presented context in which Bohr wrote these words perfectly highlights three cornerstones of this thesis:

First, paradoxes are a prevalent and universal part of human experience, whether it would be the development of theoretical physics, study of organizational behavior and decision-making, or our daily lives. As in the case of the EPR Paradox, we cannot dismiss their existence only because they go against our perceived ideas about the reality. The famous management scholar Charles Handy referred to the contemporary times as the Age of Paradox (Handy 1995) already more than 20 years ago. According to the author, ‘paradox has almost become a cliche of our times. The word crops up again and again as people look for a way to describe the dilemmas facing the governments, businesses, and, increasingly, individuals.’ (p.xi). Consequently, while most of business studies, particularly in the domain of strategy, rely on the established profit-maximization paradigm, it does not mean that it is the right paradigm to describe all the challenges facing contemporary firms.

Second, the discovery of a paradox, and above all - the acceptance of it, as Bohr rightly noted, paved the way of many new scientific discoveries that nowadays constitute a big part of physics as a scientific discipline. In a similar vein, the rich and growing body of research relying on the paradox theory (Lewis and Smith 2014) and related theories for explaining many organizational phenomena has proved that the paradox perspective can help to look at many traditionally troublesome and difficult questions from a fresh point of view. Scholars have successfully shown how paradox theory can assist in re-framing our understanding of the relationship between phenomena like science and commerce (Bednarek, Paroutis, and Sillince 2017), exploration and exploitation (Papachroni, Heracleous, and Paroutis 2015), control and collaboartion in the context of governance (Sundaramurthy and Lewis 2003), and many others. Studies so far have extensively dealt with the very nature, sources, and implications of paradoxical tensions (Poole and Van de Ven 1989; Smith and Lewis 2011). Building on that, authors have made conclusions about the leadership styles (Lewis and Smith 2014) and structures (Ebbers and Wijnberg 2017) needed in order to manage paradoxes, mindsets that help to accommodate paradoxical thinking (Miron-Spektor et al. 2017), rethorical devices (Bednarek, Paroutis, and Sillince 2017), identity work (Gotsi et al. 2010), innovation management (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009) and more. Yet surprisingly, the topic of this thesis - strategic decision-making about business models - has so far received very little conceptual and almost no empirical attention. This is hence the gap I try to fill.

Third, the main object of dispute between Bohr and Einstein - quantum entanglement - has surprisingly a lot in common with the main object of this research - strategic paradoxes. ‘Quantum entanglement is a quantum mechanical phenomenon in which the quantum states of two or more objects have to be described with reference to each other, even though the individual objects may be spatially separated.’ Strategic paradoxes, in turn, denote inherently contradictory, yet inseparable and interdependant objectives that an organization is pursuing (Bednarek, Paroutis, and Sillince 2017). In both cases we are dealing with the relationship between two (or more) interconnected elements, their influence over each other, and the way we interpret the nature and outcomes of this interaction. Although very different from each other, both theories share the idea that it is impossible and useless to observe or perform a measurement on a single part of an interrelated whole. When it comes to organizational life, this invites us to dismiss the separatist approaches, attempt to observe the integrity of processes, and embrace the uncertain, inconsistent, and paradoxical nature of strategic decision-making.

1.1.1 Framing competing strategic demands

How do we understand our world when it gets more complex than getting to A? How do we interpret what has to be done when there is more than one goal? How do we priortize, and do we, at all?

Competing strategic demands are not a new phenomenon in the management literature (Poole and Van de Ven 1989; Fairhurst et al. 2016). Many theories explicitly or implicitly have dealt with the issue, and many terms have been coined to denote such conflicts; just to name a few - dualities, polarities (Johnson 1992), dilemmas, tensions, pluralism, institutional logics. These and similar topics have been addressed in the literatures on competitive strategy, ambidexterity, tripple bottom line, innovation management, internationalization, social entrepreneurship, and others.

Yet, even though contradictions are inherent to organizational life, we have a natural tendency to strive towards consistency. Psychologists have repeatedly concluded that humans are not confortable with cognitively dissonant states (Festinger 1962). Unsurprisingly, this is also reflected in the dominant narratives of the management scholarship. Even though tensions and strategic conflicts are recognized, they are then often tackled as an optimal solution problem, using a contingency approach. A contingency approach or “if-then” thinking focuses on finding conditions in which a choice towards one or the other strategy can be consider as the optimal. But the way we interpret things changes the way we experience them, and consequently act upon them.

As argued by paradox scholars and outlined earlier in this introduction, in many situations, approaching problems from a choice perspective is impossible. The pace of development and the interconectedness of the world in the 21st has lead us to believe that we organize and manage in unprecendetly complex environments. In a reality characterized by high complexity, the ability to navigate tensions and competing demands has transformed from a peripheral skill to a neccesity. Consequently, those managers and firms that can embrace dualities, as opposed to seeking solutions, will win.

So what does a paradox perspective offer? What changes if we frame the conflicts differently? Chapter 2 tackles these questions in a thoeretical thought experiment supported by empirical evidence gathered in the qualitative stage of the field work for this dissertation.

1.1.2 Pursuing conflicting goals only outline

The negatives associated with the seeming incompatibility and complexity of the realities the managers have to deal with. Pursuing conflicting strategies is frustrating, it can trigger withdrawal, denial, cause tensions, ignorance, xxxx.

On the opposite, literature has also discussed the positives of xxx. inspiring, creativity triggering, enabling.

According to Gaim (2017), succesfully dealing with paradoxes requires specific mindsets and practices, as well as organizational-level conditions that enable them. Much research has been done recently on the mindset part (Miron-Spektor et al. 2017), as well as the organizational conditions [REF]. The empirical part of this dissertation focuses on investigating the practice-level of paradox management.

Dynamic equilibrium model of organizing: In the end, organizations need to come up with coping mechanisms, balancing acts, as “usual” decision-making strategies do not work. According to this model, strategic paradoxes create tensions, which have to be accepted and “worked through”. Paradoxical resolution requires “confronting paradoxical tensions via iterating responses of splitting and integration” (Smith and Lewis 2011). In paradox theory, these integration and differentiation (or separation) strategies are thus seen as the generic responses for coping with conflicting goals; and their application has been discovered and discussed at many levels and domains of management and organization but not at the business model level.

Integration and separation at different levels.

Chapter 3 looks more in detail in what forms can these two decision-making strategies can take, and how they are applied to business models.

1.1.3 Business modelling for complexity to do

Are these strateies equifinal? Does it matter what we choose? Are there performance implications? These questions are tackled in Chapter 4.

1.1.4 Business model heterogeneity and performance implications to do

Do differences in the importance that are attached to each of the dimensions lead to business model heterogeneity? And what are the performance implications? Chapter 5.

How can we make them fit complex strategic intents?

1.2 Same same but different: Operationalizing business models in progress, the answer to Jan’s concerns

While conventional standards would probably require this dissertation to use a consistent operationalization of the business model concept throughout all of the independent studies, instead it mirrors the plurality of the study field. The business model scholars have by now agreed on a general definition which delineates the domain studied, as well as the different possible purposes of using the concept (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah 2017). However, finding a single operationalization has proven to be impossible (Wirtz et al. 2016). Studies use very different ways of observing and measuring business models. This is also because the concept as a tool can be used for different purposes both empirically in the managerial practice(Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010).

While staying true to the conventional definition and domain delineation which relies on four domains in which decision can be made - value proposition, value delivery, value creation, and value capture, each of the papers in this thesis in fact looks at the business model from a slightly different perspective (see Table 1.1).

- Chapter 3: the purpose of decision making

- Chapter 4: the extent to which they integrate of differentiate paradoxical considerations

- Chapter 5: specific decisions that compose a business model, based on which we derive a taxonomy

1.3 Purpose and overview of the thesis

| Chapter | Research Question | Research Approach | Data | Contributions | Business model conceptualization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Thriving off of Tensions | How can paradox perspective enrich creative industries research? | Conceptual with empirical support | - | The identification of an alternative conceptual framework for framing and studying tensions in the creative industries context; | - |

| 3 Crafting Business Models for Paradoxical Goals | How do firms use business model design in order to attend strategic paradoxes? | Qualitative, inductive, cross-case analysis | In-depth interviews (n=16), expert panels, field notes | The identification of a menu of business model related decisions that can be used to address paradoxical strategies simultaneously; Paradox management at the business model level’ | Process of decision-making |

| 4 Killing Two Birds with One Business Model | How do integration and separation decisions within different business model elements lead to (mis-) balanced performance in conflicting domains? | Combined qualitative and quantitative, configurational analysis (using Qualitative Comparative Analysis) | In-depth interviews (n=16), survey data (n=179), expert surveys (n=4) | A configurational perspective to paradox management; Empirical evidence for inter-relatedness of business model elements; | Configurations of integration and differentiation decisions |

| 5 Organizational commitments to conflicting values, business models and performance | How do organizational values influence business model heterogeneity, and what are the joint performance implications? | Quantitative, deductive, factor analyses, QCA Survey data | (n=196) | Explaining business model heterogeneity as a result of different value profiles, and linking them to performance outcomes; | Empirically derived taxonomy |

1.4 A note on methodology: Studying organizations as configurations in progress, for now copied from the earlier versions of P2

While on a theoretical level this thesis brings together paradox theory and business model literature, at the methodic level, I make use of the configurational theory and the methods developed with in the field. Since it is not a traditional perspective used in management studies, even though upcoming and often implied, I assume it requires some explaination as to 1) how it is relevant for this thesis? and 2) what it means to study organizational phenomena as configurations. This section also complements the method sections of Chapters 4 and 5, giving a broader contex and extra insights into the workings of QCA than possible within the limits of a single paper.

1.4.1 Configurations and QCA for business model research

Configurational perspective is based on the assumption that “cases under study [are] constellations of interconnected elements” (Misangyi et al. 2017, 256). QCA belongs to a family of comparative configurational methods (CCM) that allows for a systematical analysis of comparable cases to identify causally relevant structural conditions (variables) that lead to an identified outcome (Marx et al. 2013; Thiem, Baumgartner, and Bol 2015).

QCA is a set-theoretic method, employing a causes-to-effects approach to examine combinations of causal conditions (sets) instead of the more traditional search for linear causation (Mahoney and Goertz 2006). The method thus assists in answering questions that imply configurations, e.g. what conditions (X, Z, etc.) combine to cause an outcome (Y)? More precisely it looks at what conditions or combinations of conditions are necessary and/or sufficient for an outcome to occur. Necessary conditions are present whenever we observe an outcome. Sufficient conditions are conditions that display the presence of an outcome whenever the conditions are present. As all configurational methods, also QCA is based on three main assumptions: 1) relationships to outcomes are nonlinear and asymmetric; 2) variables that are causally related in one configuration are not necessarily related in others, implying complex causality; and 3) configurations can be equifinal (Fiss 2011, 2007).

The two following observations led to concluding that configurational approach is the most appropriate for our analytical framework: 1) The conceptualization of business models as a set of decision variables makes it a naturally configurational concept; 2) Both paradox theory and business model perspective oppose the contingency theory assumptions, i.e. “if-then” and “net-effects”, and instead look at the interaction between structures and practices and assume equifinality - idea that multiple configurations can have similar outcomes (Fiss et al. 2013; Nenonen and Storbacka 2010; Lewis and Smith 2014; Täuscher 2017).

Despite the apparent fit, not much configurational work exists in both areas. Even less so when it comes to linking the two streams. In paradox scholarship, the idea that organizations need both integrating and separating strategies is rather new, therefore not much research beyond theory building exists. In the case of business models, there has been a lack of methods that can empirically do justice to the complexity and configrutional nature of the concept. The lack of appropriate analytical tools has been a general problem of naturally configurational concepts. However, as argued by Fiss (2007) and Misangyi et al. (2017), the development of methods such as QCA has given rise to neoconfigurational perspective, allowing embracing causal complexity appropriately. These developments have paved the way to some recent applications of QCA in business model literature (Täuscher 2017; Kulins, Leonardy, and Weber 2016; Aversa, Furnari, and Haefliger 2015).

1.4.2 The process of fuzzy set QCA

QCA is case-oriented, as opposed to the variable-oriented methods (Marx et al. 2013). When applying QCA in organization studies, variables (referred to as conditions in QCA) are defined in terms of sets of organizational attributes. The choice of conditions can be both theoretical and empirical, namely, based on the knowledge of cases and the setting (Schneider and Spieth 2013). A set can be a single condition (e.g., client segmentation) or a combination of conditions (e.g., high creative AND business performance). Each case (firm’s survey response, in our case) is expressed in terms of its membership to the defined sets. The process of transforming gathered raw data about cases into membership scores is called calibration (Thiem and Dusa 2013). It prescribes the definition of three qualitative thresholds: full membership, the cross-over point, and full non-membership. The crossover point, contrary to most accepted measurement scales, establishes a difference in kind, not degree. It is the score that indicates the point of maximum ambiguity, when a firm has both a degree of membership and non-mebmerhsip of 0.5 in the given set (Jacobs 2017). For this study, we have chosen to carry out a fuzzy set QCA (fsQCA). In fsQCA cases are not only expressed in their full membership to the sets (1 is in, 0 is out), but also partial memberships can be assigned (partially in, partially out).

When the data is calibrated into sets, a truth table is computed. It is the main analytical device of QCA. It shows all the possible combinations of the defined conditions (for five conditions that would mean 32 possible combinations), also those that are not observed in the data. Each row of the table represents a unique configuration. To identify the configurations leading to the defined outcome, the truth table is futher minimized or reduced performing a systematic cross-case analysis based on Boolean algebra (Rihoux and Ragin 2009). In order to do so, the researcher has to: 1) set the tresholds of consisitency and frequency for rows to be allowed in the minimization, 2) specify the assumptions about directionality of the relationships between conditions and outcome, and about easy and difficult counterfactual analysis will be performend (Enhanced Standard Analysis), and 3) evaluate the model based on parameters of fit (Schneider and Wagemann 2012).

Consistency indicates the “degree to which a proposition about the sufficiency/necessity of a condition for an outcome is true.” (Thiem and Baumgartner, n.d.) It can have a value between 0 and 1. If the score is low, we cannot deem that a configuration is sufficient/neccessary, as it is not supported by empirical evidence. Frequency treshold refers to the number of empirical observations that display the specific configuration, in order for it to be inlcuded in the minimization.

In addition, three other parameters of fit assist in evaluating the model - coverage, proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) and relevance of neccessity (RoN). Coverage shows the percentage of cases observed for which the configuration is valid. Low coverge, as opposed to the case of consistency, does not indicate the irrelevance of the configuration, it is simply represented by few empirical instances. PRI shows the degree to which the specific configuration (or the whole solution) is not simultaneously sufficient for the presence of the outcome, as well as its absence. RoN is a measure of triviality that shows how close a conditions is to a constant (Schneider and Wagemann 2012; Thomann and Maggetti 2017). Table ?? shows an overview of the main possible issues in model evaluation and the ways we dealt with them.

In the minimization procedure, there are three search strategies that are applied each producing different solution types (Ragin 2009; Thiem and Baumgartner, n.d.; Schneider and Wagemann 2012). According to Ragin (2009), a thorough QCA produces all three of them in each analysis. The complex solution shows the configurations that are sufficient for the outcome without any counterfactual analysis, meaning, based only on the empirically observed instances, no logical reminders are included. The parsimonious solution on the contrary includes all the logical remainders, without evaluating their plausibility. This solution term is considered the most causally relevant, as it shows the largest solutions sets. The intermediate solution requires the researcher to make several evaluations: 1) in the unobserved configurations, are the conditions expected to contribute to the outcome in their presence or absence? (directional expectations based on theory), 2) are there any instances where the same rows are found to be sufficient for both the presence of the outcome and its absence?(easy counterfactuals)?, and 3) can / should conditions be removed in parsimonious solution based on substantial knowledge about them (difficult counterfactuals)?

In line with the currently accpeted standards of good practice in QCA (Ragin 2009; Fiss 2011; Thomann and Maggetti 2017), we report both core (⚫for presence and ⦻ for absence) and peripheral conditions (●for presence and ⦸ for absence). The peripheral conditions represent the ones present in the intermediate solutions, and the core conditions are the ones present in both the intermediate and parsimonious solutions. Blank spaces in the table indicate that in the given solution the condition is not causally relevant.

References

Andriopoulos, Constantine, and Marianne W. Lewis. 2009. “Exploitation-Exploration Tensions and Organizational Ambidexterity: Managing Paradoxes of Innovation.” Organization Science 20 (4): 696–717.

Aversa, Paolo, Santi Furnari, and Stefan Haefliger. 2015. “Business Model Configurations and Performance: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis in Formula One Racing, 2005–2013.” Industrial and Corporate Change 24 (3). Oxford University Press: 655–76.

Baden-Fuller, Charles, and Mary S. Morgan. 2010. “Business Models as Models.” Long Range Planning 43 (2): 156–71.

Bednarek, Rebecca, Sotirios Paroutis, and John Sillince. 2017. “Transcendence Through Rhetorical Practices: Responding to Paradox in the Science Sector.” Organization Studies 38 (1). SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England: 77–101.

Casadesus-Masanell, Ramon, and Joan E. Ricart. 2011. “How to Design a Winning Business Model.” Harvard Business Review 89 (1/2): 100–107.

Ebbers, Joris J, and Nachoem M Wijnberg. 2017. “Betwixt and Between: Role Conflict, Role Ambiguity and Role Definition in Project-Based Dual-Leadership Structures.” Human Relations. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 0018726717692852.

Einstein, Albert, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen. 1935. “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?” Physical Review 47 (10). APS: 777.

Fairhurst, Gail T, Wendy K Smith, Scott G Banghart, Marianne W Lewis, Linda L Putnam, Sebastian Raisch, and Jonathan Schad. 2016. “Diverging and Converging: Integrative Insights on a Paradox Meta-Perspective.” Academy of Management Annals 10 (1). Academy of Management: 173–82.

Festinger, Leon. 1962. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Vol. 2. Stanford university press.

Fiss, Peer C. 2007. “A Set-Theoretic Approach to Organizational Configurations.” Academy of Management Review 32 (4): 1180–98.

———. 2011. “Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research.” Academy of Management Journal 54 (2): 393–420.

Fiss, Peer C., Bart Cambre, Axel Marx, Peer C. Fiss, Axel Marx, and Bart Cambr?? 2013. “Chapter 1 Configurational Theory and Methods in Organizational Research: Introduction.” Configurational Theory and Methods in Organizational Research (Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Volume 38) Emerald Group Publishing Limited 38: 1–22.

Gaim, Medhanie. 2017. “Paradox as the New Normal: Essays on Framing, Managing and Sustaining Organizational Tensions.” PhD thesis, Umeå universitet.

Gotsi, Manto, Constantine Andropoulos, Marianne W. Lewis, and Amy E. Ingram. 2010. “Managing Creatives: Paradoxical Approaches to Identity Regulation.” Human Relations.

Handy, Charles. 1995. The Age of Paradox. Harvard Business Press.

Jacobs, Sofie. 2017. “A Configurational Perspective on Success in Small-Sized Creative Organizations.” PhD thesis, University of Antwerp.

Jarzabkowski, Paula, Jane Le, and Andrew H Van de Ven. 2013. “Responding to Competing Strategic Demands: How Organizing, Belonging, and Performing Paradoxes Coevolve.” Strategic Organization, 1476127013481016.

Johnson, Barry. 1992. Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems. Human Resource Development.

Kulins, Christopher, Hannes Leonardy, and Christiana Weber. 2016. “A Configurational Approach in Business Model Design.” Journal of Business Research 69 (4). Elsevier: 1437–41.

Lewis, Marianne W., and Wendy K. Smith. 2014. “Paradox as a Metatheoretical Perspective: Sharpening the Focus and Widening the Scope.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 0021886314522322.

Mahoney, James, and Gary Goertz. 2006. “A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research.” Political Analysis 14 (3): 227–49.

Marx, Axel, Bart Cambre, Benoit Rihoux, and Peer C. Fiss. 2013. “Chapter 2 Crisp-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis in Organizational Studies.” Configurational Theory and Methods in Organizational Research (Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Volume 38), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 23–47.

Massa, Lorenzo, Christopher L Tucci, and Allan Afuah. 2017. “A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research.” Academy of Management Annals 11 (1). Academy of Management: 73–104.

Miron-Spektor, Ella, Amy Ingram, Josh Keller, Wendy Smith, and Marianne Lewis. 2017. “Microfoundations of Organizational Paradox: The Problem Is How We Think About the Problem.” Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management, amj–2016.

Misangyi, Vilmos F, Thomas Greckhamer, Santi Furnari, Peer C Fiss, Donal Crilly, and Ruth Aguilera. 2017. “Embracing Causal Complexity: The Emergence of a Neo-Configurational Perspective.” Journal of Management 43 (1). SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: 255–82.

Nenonen, Suvi, and Kaj Storbacka. 2010. “Business Model Design: Conceptualizing Networked Value Co-Creation.” International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 2 (1). Emerald Group Publishing Limited: 43–59.

Papachroni, Angeliki, Loizos Heracleous, and Sotirios Paroutis. 2015. “Organizational Ambidexterity Through the Lens of Paradox Theory Building a Novel Research Agenda.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 51 (1): 71–93.

Poole, Marshall S., and Andrew H Van de Ven. 1989. “Using Paradox to Build Management and Organization Theories.” Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 562–78.

Ragin, Charles C. 2009. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond. University of Chicago Press.

Rihoux, Beno??t, and Charles C. Ragin. 2009. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Qca) and Related Techniques. Sage.

Schneider, Carsten Q, and Claudius Wagemann. 2012. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Schneider, Sabrina, and Patrick Spieth. 2013. “Business Model Innovation: Towards an Integrated Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Innovation Management 17 (01): 1340001.

Smith, Wendy K, Michael Gonin, and Marya L Besharov. 2013. “Managing Social-Business Tensions: A Review and Research Agenda for Social Enterprise.” Business Ethics Quarterly 23 (3). Cambridge University Press: 407–42.

Smith, Wendy K., and Marianne W. Lewis. 2011. “Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing.” Academy of Management Review 36 (2): 381–403.

Sundaramurthy, Chamu, and Marianne Lewis. 2003. “Control and Collaboration: Paradoxes of Governance.” Academy of Management Review 28 (3). Academy of Management: 397–415.

Täuscher, Karl. 2017. “Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis and System Dynamics for Theory-Driven Business Model Research.” Strategic Organization. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 1476127017740535.

Thiem, Alrik, and Michael Baumgartner. n.d. “Glossary for Configurational Comparative Methods.”

Thiem, Alrik, Michael Baumgartner, and Damien Bol. 2015. “Still Lost in Translation! A Correction of Three Misunderstandings Between Configurational Comparativists and Regressional Analysts.” Comparative Political Studies, 0010414014565892.

Thiem, Alrik, and Adrian Dusa. 2013. “Boolean Minimization in Social Science Research: A Review of Current Software for Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Qca).” Social Science Computer Review, 0894439313478999.

Thomann, Eva, and Martino Maggetti. 2017. “Designing Research with Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Qca) Approaches, Challenges, and Tools.” Sociological Methods & Research. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 0049124117729700.

Wirtz, Bernd W, Adriano Pistoia, Sebastian Ullrich, and Vincent Göttel. 2016. “Business Models: Origin, Development and Future Research Perspectives.” Long Range Planning 49 (1). Elsevier: 36–54.

For intance, many sector specifc surveys of the Economist Business Intelligence Unit confirm this statement http://www.eiu.com/home.aspx#about ↩

Design consultancies, architecture firms, advertisement companies, firms providing audiovisual services, digital agencies and similar firms.↩