Chapter 4 KILLING TWO BIRDS WITH ONE BUSINESS MODEL:

UNRAVELING SUCCESFUL CONFIGURATIONS FOR ACHIEVING CONFLICTING PERFORMANCE GOALS1

Abstract. Contemporary firms often have to work towards achieving contradictory performance-criteria, which leads to designing complex business models. Despite the urgency of the topic, little empirical work exists in exploring the workings of business models for dual agendas. Based on prior literature on ambidexterity, paradox management and business model components, we build a model that defines business models as configurations of decisions that aim at either integrating the two conflicting performance goals, or separating them. More precisely, we explore the interplay between five business model level decisions - portfolio differentiation for different aims (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009), (paradoxical) client segmentation (Bednarek et al. 2016), finding complementary partners (Yunus, Moingeon, and Lehmann-Ortega 2010), multi-sided revenue models (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010), and structural venture separation (Markides and Charitou 2004). Our study is based on a comparative case survey of business modelling practices of 179 Dutch creative service firms (i.e., design agencies, advertisement firms, architecture firms). Using fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA), we identify which configurations of the five differentiation strategies are necessary and/or sufficient for performing well in two conflicting domains simultaneously, in our case - creative and business success, and which lead to a misbalance towards either creative or business performance, or both.

4.1 Introduction

"Interviewee:Big clients subsidise small clients.

Interviewer:What value do you get from the small then?

Interviewee:Love.’

– Anonymous interview respondent

The business model has proven to be a useful concept for explaining how firms create value (Magretta 2002) and outperform each other (Afuah 2004; Zott and Amit 2007). According to the business model perspective, they do so by converting their goals (Smith, Binns, and Tushman 2010) into better-performing configurations of decisions about value propositions, target markets, value creation mechanisms and revenue models (Baden-Fuller and Mangematin 2013; Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) than those of their competitors. While viewing firms in terms of business models has helped managers, as well as researchers to understand and articulate better the processes of value creation and capture, the literature has been surprisingly over-focused on explaining the economic value creation (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah 2017), and very limited attention has been paid to understanding business models in cases were firms have to generate other value than profit.

As recently discussed in various theoretical domains such as paradox theory, institutional logics, organizational pluralism, or triple-bottom line, more and more contemporary firms are compelled to satisfy competing, even conflicting performance criteria at the same time (Bednarek, Paroutis, and Sillince 2017, @Besharov2014). The common examples of other performance goals alongside profit-making include social (Smith, Gonin, and Besharov 2013) and environmental missions (Dixon and Clifford 2007), corporate social responsibility (Wong and Dhanesh 2017), multiple stakeholder satisfaction (Jarzabkowski, Le, and Van de Ven 2013), or creative performance, as in the case of the research setting of this study - the creative service firms (Jacobs 2013). The long-term success and competitive advantage of firms facing conflicting demands depend heavily on their ability to strike a balance in these different domains (Smith 2014). The question is then - how can firms build business models that are able to manage conflicting goals simultaneously?

One can find empirical and theoretical propositions on different strategies for managing conflicting goals applicable at the business model level in prior literature on corporate venturing, business models, and paradox management. Markides and Charitou (2004) have explored the conditions under which it would beneficial to create separate ventures for business models having different strategic intents. Andriopoulos and Lowe (2000) observed that design firms shift between projects aimed at financial goals and employee satisfaction; DeFillippi (2015) argued that in the context of media companies, portfolio diversification can help firms to tackle the ambidexterity challenge; Yunus, Moingeon, and Lehmann-Ortega (2010) discussed the benefits of separate social and marketing networks in the context of social enterprises; Grassl (2012) examined the use of different revenue mechanisms for different client groups in hybrid organizations.

While the identified strategies undoubtedly can help firms to grapple the challenge of satisfying multiple performance criteria simultaneously, it is unknow how they combine. Given their interdependent nature, such “design choices in business model components cannot be considered in isolation but should be balanced in order to develop a viable business model” (Haaker, Faber, and Bouwman 2006). It is thus the aim of this article to unravel how these different business model level strategies combine for high performance in pluralistic (dual performance) settings.

In order to reach our research objective, we first leverage insights from paradox literature to build a conceptual framework of business modelling for conflicting goals. According to paradox theory, integration and separation are the two generic organizational and individual responses to conflicting demands. We examine prior studies that show how these are applied with respect to four business model elements - content of the value proposition, client and market selection, network organization, and revenue model. Based on prior studies on ambidexterity, we also include two organization-level variables, namely, venture separation and integrated culture as a variable in our analyses. We study survey data on business modeling practices of 179 Dutch creative service firms. Using fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) (Ragin 2009), we examine 1) how the identified differentiation strategies at different business model domains combine for achieving high creative and commercial performance; 2) which configurations can explain performing low on one or both of the conflicting dimensions.

The contribution of this paper is three-fold: 1) The findings deepen our understanding of business models, emphasizing that specific business model elements change their importance in combination with other elements. Our results show the different business modelling paths that lead to success and failure in strategically pluralistic settings; 2) Partially confirming expectations in paradox research, we show that a mix of differentiating and integrating strategies are needed to succeed (and to fail); 3) The study shows how neoconfigurational methods can be used in order to study business models beyond single cases.

The remainder of the paper unfolds as follows: first, we combine business model and paradox literature to build the conceptual model and formulate hypotheses. Second, the data, sample, and the suitability and application of configurational methods are explained. Finally, we discuss the results, conclusions, and implications for further research and practice.

##Theoretical background and conceptual framework In order to build our conceptual model, we embed the study of business models in two increasingly prominent meta-theoretical approaches, namely, paradox theory (e.g. Poole and Van de Ven 1989; Schad et al. 2016; Smith and Lewis 2011) and configurational theory (Fiss et al. 2013; @;jh??aMisangyi2017; Snow, Miles, and Miles 2006). Paradox theory provides a lens for understanding how business models can serve as a device for managing conflicting demands. Configurational approach offers both theoretical and methodic tools that allow for better conceptualization and analysis of business models and their relationship to paradoxes. In this section, we explain how we connect the first two perspectives. Configurational approach is discussed in the methods section.

###Business models and firm performance

A business model explains how firms “create, deliver and capture value” (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010, 14). More specifically, it can be defined as “the design by which an organization converts a given set of strategic choices - about markets, customers, value propositions - into value, and uses a particular organizational architecture - of people, competencies, processes, culture and measurement systems - in order to create and capture this value” (Smith, Binns, and Tushman 2010, 450).

Studying firms from a business model perspective emerged as an alternative way of conceptualizing and describing how firms do business (Magretta 2002). When compared to earlier perspectives, such as resourced-based view or industrial organization, the business model perspective focuses on “voluntary choices over environmental conditions” (Demil et al. 2015). The business model thus reflects the decisions firms make about their products, markets, resource organization and revenue models. By making these decisions, firms create mechanisms or systems that transform their strategic goals and needs into value.

While a considerable body of work has been dedicated to developing component-based conceptual frameworks for the study of business models (Osterwalder, Pigneur, and Tucci 2005; Wirtz et al. 2016), no agreement on one single conceptualization has been reached among the scholars. Notwithstanding the disagreements, in line with the given definitions, most studies commonly distinguish four basic domains or components of business models:

- Value proposition describes the basic features of the offering, the type of value it is generating and the perceived basis of differentiation from competitors.

- Value delivery describes the demand side or the customer infrastructure that the firm builds - its target markets and customers to whom the value is delivered; how they are acquired and reached.

- Value creation depicts the supply side of the firm, namely, what internal and external resources, activities and structures are needed to create the value proposition.

- Value capture describes the financial aspects of the firm’s value mechanisms (Morris, Schindehutte, and Allen 2005; Osterwalder, Pigneur, and Tucci 2005; Teece 2010).

Research, as well as evidence from the practice show that successful combinations of decisions in these four domains can grant firms advantage over competitors and explain performance differentials (Zott and Amit 2008, @Zott2007). This can take place in different ways. Firms can use superior business model designs upon the commercializing of new technology (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002). Business models can also be subject to innovation themselves, as firms either create new ways of delivering and capturing value in established industries (Mason and Spring 2011; Teece 2010), or respond to the changes in their competitive environments through business model adaptation (Volberda and Lewin 2003). Some authors have even gone so far to say that the future quest of sustainable competitive advantage lies in business models (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2011). However, just as most of the strategic literature (De Wit and Meyer 2010), also the literature on business models has largely ignored the fact that firms might have a purpose beyond profit-maximization (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah 2017). Apart from setting-specific studies in fields like social entrepreneurship (Grassl 2012) or sustainability (Bohnsack, Pinkse, and Kolk 2014), business models are mostly studied as strategic decisions that help to create economic value (Magretta 2002).

4.1.1 Organizational goals, pluralism and paradoxes of performing

Despite the dominance of profit-maximization paradigm, firms increasingly aspire or are compelled to create other value than the economic, e.g. social, stakeholder, environmental, and hence are pursuing several performance objectives simultaneously. Diverse research agendas have addressed this phenomenon, including institutional theory, triple-bottom-line, and organizational hybridity. Since our interest lies in the way managers make strategic decisions about business models, particularly, when there are conflicts and incompatibilities across the demands firms face, we leverage literature on pluralism and organizational paradoxes.

The concept or organizational pluralism is used to describe contexts that are characterized by “multiple objectives, diffuse power and knowledge-based work processes” (Denis, Langley, and Rouleau 2007, 180). Pluralism arises as a result of “the divergent goals and interests of different groups, each of which have sufficient power bases to ensure that their goals are legitimate to the strategy of the organization” (Jarzabkowski and Fenton 2006, 631). Pluralism can find its source both within and outside the organization. For instance, in the case of professional service firms (also our research setting), the need to retain highly skilled employees often requires managers to act against the market interests, as the profitable work is not always the most interesting one, but the skilled professionals need to be challenged enough to be motivated to perform well (Teece 2003). In hybrid organizations, such as hospitals or universities, competing demands are created by the need to satisfy different stakeholder groups like funding bodies, regulatory institutions, and different client groups (Denis, Langley, and Rouleau 2007).

While most settings exhibit some levels of pluralism, in particularly salient settings, it can create what paradox scholars refer to as performing or strategic paradoxes - “contradictions in organizational objectives based on the divergent definitions of success held by important stakeholders” (Bednarek, Paroutis, and Sillince 2017, 80). Strategic paradoxes are characterized by conflict, incompatibility, and interdependence (Jarzabkowski, Le, and Van de Ven 2013). The multitude of stakeholders and competing goals surface tensions as the individuals struggle to make conflicting decisions, and carry out conflicting tasks and roles simultaneously (Jarzabkowski, Le, and Van de Ven 2013; Luscher and Lewis 2008). Moreover, since they are all legitimate, making choices is impossible. To examplify, scientific institutions face strategic paradoxes, as their sustainability depends on the long-term ability of producing excellent research, as well as the short-term immediate capacity of creating societal and commercial impact by providing educational services and commercializing research results (Bednarek, Paroutis, and Sillince 2017). Other examples of settings in which strategic paradoxes are dominant include the ambidextrous firms, social enterprises, learning organizations (Smith, Binns, and Tushman 2010), and also the setting of this study - the creative industries firms, whose success is defined both in creative and commercial terms, yet each requires conflicting decisions, resources and structures to be implemented (DeFillippi, Grabher, and Jones 2007; Jacobs 2012).

Strategic paradoxes are particularly influential for they penetrate the whole organization, having immediate implications for management and organization, and thereby determine firm performance and the ability to sustain itself in the long run (Jarzabkowski and Fenton 2006; Smith 2014). With respect to performance evaluation, strategic paradoxes create what we could call the double-success criterion (Jacobs 2013). Literature on social entrepreneurship, corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and triple-bottom-line has argued that performance measures in such increasingly complex settings have to be extended beyond profit to include measures concerning, for instance, social performance, environmental performance, markets, customers, internal processes, and learning and development (Hubbard 2009). The question within the context of our research is - how can business model design assist firm in achieving conflicting performance goals?

4.1.2 A paradox approach to business models: The conceptual framework

Figure 4.1 illustrates the assumed relationship between organizational goals business models and firm perfromance under the classic profit-maximization paradigm. This is the way most business model literature studies business models.

Figure 4.1: Business modelling for profit maximization.

According to paradox scholars, complex strategic demands and aspirations require designing “complex business models” that would be able to accommodate the confliciting demands (Smith, Binns, and Tushman 2010). The business model literature holds no immediate answers explaining the workings of such complex business models. To build the conceptual framwork, we levarage three key insights from paradox theory.

First, not all strategic conflicts can be framed in terms of choice. According to the literature on pluralism, since all of the conflicting objectives are legitimate, a choice cannot and should not be made. Instead, firms have to adopt what is referred to as the “both/and” approach to managing (Smith 2014). It opposes the more traditional contingency approaches and trade-off thinking, which imply that strategic conflicts can only be resolved by a choice. “The core premise is not problem solving through fit, but coexistence”(Lewis and Smith 2014, 3). According to the “both/and” perspective, success of firms that face strategic paradoxes will depend on their ability to accept the paradoxical nature of their objectives and learning how to cope with them. As paradoxes are not only conflicting, but also interdependent and persistent over time, making choice in favor of one objective would never solve the situation, as the other neglected objective would resurface eventually. This means that instead of solving situations, paradoxes have to be managed (Smith and Lewis 2011). Empirically, it implies that in salient settings, we consider paradoxes as given and do not attempt to measure them.

Second, managing paradoxes implies enacting a balancing act with respect to setting goals and evaluating performance. According to our qualitative interviews, in practice a success situation is reached when the performance in all relevant domains over time is 1) above the “break-even” point, and 2) equally well-attained. The operationalization of performance balance in this study is further discussed in the methods section.

Third, paradox theory offers meta-thoeretical models explaining the ways managers apply considerations about conflicting goals in their decision-making. According to most paradox research (Smith and Lewis 2011), there are the two generic approaches a firm can adapt in its decisions, structures, and contexts in order to cope with paradoxes - integration and separation (or differentiation). Differentiation approach to paradox management prescribes dealing with tensions through segmentation and/or source splitting, e.g. establishing separate units, teams, even ventures, leadership structures, processes, segmenting and shifting between activities over time (Poole and Van de Ven 1989; Fairhurst et al. 2016). Integration approach implies searching for compromise in terms of middle-way or solutions that embrace both poles, e.g. hiring all-around employees that adhere to both visions (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013), or building common organizational value system through communication of strategic goals (Kolsteeg 2014).

Figure 4.2: Business modelling for conflicting goals.

When synthesizing these insights conceptually, the process of business model design changes from that presented in the Figure 4.1 to a more complex one, presented in Figure 4.2. Visually, the only difference between business modelling for profit-maximization and for strategic paradoxes is the addition of an extra goal dimension, and, consequently, an extra performance dimension. However, the fact that more than one goals is driving decision-making and potentially even creating conflicts changes as seemingly incompatible decisions might be made, changes the very nature of the business modelling process. While in the first case business model design can be viewed as a process of optimizing, in the second it resembles for a process of compromising and balancing. The goals are expected to be directly reflected in the business model decisions, and they can either accommodate both goals simultaneously (integrate) or separately (differentiate). This would not be the case, in case there would be only one goal.

4.2 The analytical model and hypotheses

As already highlighted in the introduction, there is evidence in prior literature that firms use the integration and separation strategies with respect to the decisions that compose their business models. The studies are slightly “hidden” in that they usually lack one of the theoretical components of our study - either they rely on paradox theory and only implicitly discuss some aspects of business modelling (Andriopoulos and Lowe 2000; DeFillippi 2015, 2009), or they study business models in the light of similar questions as discussed in the paradox literature, without using the paradox theory to explain them (Markides and Charitou 2004; Markides 2013; Yunus, Moingeon, and Lehmann-Ortega 2010). In order to build our framework, we searched literature for evidence of firms using differentiation / integration strategies in the general domains of business models outlined previously - content of value proposition, clients and markets, resource organization (aka value creation) and revenue model. Some insights on how this takes place also came from our interviews. Interestingly, at the business model level, we found only differentiation strategies discussed. We selected four most common strategies to use in our analyses. We equally included two organization-level variables in our model - integrated organizational culture and structural venture separation. These have been the main focus of most ambidexterity literature (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013), and will be analyzed as contextual conditions. We elaborate on this further.

4.2.1 Portfolio diversification

Internal to firm, one of the main business model choices for firms is that of their value offering - the portfolio of services and/or products that they provide. Prior research in ambidexterity (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009) and creative industries (Bettiol, Di Maria, and Grandinetti 2012; DeFillippi 2015) has shown that diversifying the portfolio to include offering that tackle the different strategic intents separately can help to effectively target conflicting performance objectives. Earlier research in innovation management (Wheelwright and Clark 1992) has similarly suggested “aggregate project plans” that would include both profitable and high-risk projects. Moreover, not only has research found evidence to diversification in terms of horizontal offering, but also adding extra value chain activities to address different needs (Winterhalter, Zeschky, and Gassmann 2016).

4.2.2 Client segmentation

According to Teece (2010), client selection is the most crucial business model choice. Even in enterprises that have single strategic intents dual client segments are not uncommon, especially in platform models where one user group gets a service for free, while another segment pays for the access to this user base (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010). In the context of ambidexterity of knowledge intensive firms, Bednarek et al. (2016) demonstrated that client segmentation allows to tackle both exploration and exploitation over time through acquiring different knowledge in different client relationships. Similarly, Andriopoulos (2003) found evidence that managers in NPD design firms switch between different types of clients that are either commercially, or creatively interesting.

4.2.3 Network differentiation

Another way of attending to dual goals in the business model is through acquiring resources for the different strategic intents through separate networks. Yunus, Moingeon, and Lehmann-Ortega (2010) illustrated this strategy in the case of business modelling for social enterprises. The authors argued that in order to build both social and commercial value, it is vital to attract complementary partners that have the skills and now-how not readily available to the firm. The research of Kauppila (2010) demonstrates the importance of structural separation of interorganizational partnerships for maximizing conflicting strategic intents. Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (2013) have discussed this in more theoretical terms, suggesting that two-sidedness at the value offering of business models also requires two-sided value chains and networks.

4.2.4 Dual revenue models

Finally, benefits of separation have also been underlined with respect to revenue models, where different types of monetization would be applied for groups providing different value for the firm. For instance, the one-for-one revenue model of social enterprises like TOMS has showed how different intentions can be reach through different payment (or free) versions for different groups that cross-subsidize each other (Marquis and Park 2014). In more traditional profit settings, Andriopoulos and Lewis (2009) exemplified how firms would do own investments in more innovative projects, while stick to classic budgeting practices for the more commercial ones.

4.2.5 Venture separation and integrated culture

While the presented business-model-level strategies are the focus of this study, we cannot ignore the earlier work at the organizational level. Probably the most important discussion on pursuing conflicting goals has dealt with the concepts of structural ambidexterity versus contextual ambidexterity (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). The former refers to the practice of creating separate units or even ventures for pursuing innovation activities, such as R&D, as opposed to exploitation activities (O’Reilly 3rd and Tushman 2004). The latter argues that structural separation risks with complete disintegration and hence failure, if not embedded in an organizational culture that stresses the synergy between two conflicting performance goals in an integrated manner (Kauppila 2010; Jansen et al. 2009). In line with this, Burgers et al. (2009) showed that the success of corporate venturing is higher if structural separation is combined with integration at the leadership level. We can thus formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Whenever venture separation is present, integrated organizational culture should also be present achieving both high creative and commercial performance.

In the business model literature, this issue has been addressed under the discussion of whether business models that are designed for different competitive strategies can be accommodate in a single firm or not. According, to Markides and Charitou (2004), “separation is the preferred strategy when the new market is not only strategically different from the existing business but also when the two markets face serious tradeoffs and conflicts.” (p.24) The authors further argue that in cases where strategic intents and markets are similar, the existing infrastructure and the business model of the focal firm is enough. Since, in the case of paradoxical strategies, there is a conflict, we could expect that firms who have spun off either commercial or creative activities in other affiliated ventures will be able to score high on both performance dimensions. Accordingly, if they have not done so, they will require implementing other strategies in their business models that allow them to cope with the strategic paradox. This brings us to the second hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: The absence of paradoxical venture separation will require other differentiating paradox management strategies to be implemented at the business model of the focal firm (INUS condition) for the firms to be succesful at both performance dimensions.

Hypothesis 2b: The presence of paradoxical venture separation will require other differentiating paradox management strategies at the business model to contribute to the success in their absence (INUS condition).

Since the conceptual framework has not been previously tested, it is impossible to formulate precise configurational hypotheses about the relationship between the different business-model-level variables in our model. While most of the business model research would suggest that the last four differentiation strategies outlined before would have to be all implemented in the same time, thus creating two-sided business models (Baden-Fuller and Mangematin 2013), literature also argues that the multi-sidedness throughout the business model is very complex to implement successfully (Parmentier and Gandia 2017). In accordance with this conclusion, more recent studies in paradox management research suggest that it not enough to apply only differentiation strategies (Smith 2014). Paradoxically, in order to balance conflicting strategic intents, both integration and differentiation are needed. Differentiating allows understanding the individual contributions and demands of each strategic goal, while integrating motivates finding ways to link the two. If both are not used, one of the functions is missing and the firms fail to continuously commit to both poles.

While we did not find much discussions on integration strategies applied at the business model level, hence also they are absent from our model, we can expect that the absence of the implementation of a differentiation strategy means that the firm is at least to some extent trying to integrate both conflicting goals in its decision-making about business models. Combining these insights, we can formulate the following general hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Balanced performance patterns will be result from business model designs that rely on a mix of both presence and absence of differentiation strategies.

Hypothesis 3b: Unbalanced performance patterns will result from business model designs that only rely on presence or absence of differentiation strategies.

Finally, given the interdependent nature of business modelling decision, we also expect that no single variable is individually necessary and or sufficient for reaching high performance in both domains. This means that we expect all configurations to consist of at least two conditions. This property of variables only jointly forming sufficient configurations is referred to INUS nature of a condition (variable) in QCA - insufficient but nonredundant parts of different configurations, which are themselves unnecessary but sufficient for the occurrence of the outcome (Fiss et al. 2013). Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 4: Portfolio diversification, client segmentation, network differentiation, and dual revenue models are INUS conditions for achieving high creative and commercial performance simultaneously.

4.3 Methods and data

As mentioned in the introduction, this study takes a configurational perspective to organizational success. In order to reach our research objective, we carried out a particular form of configurational analyses - the fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). We investigated how the four business model design choices - portfolio diversification, client segmentation, differentiated network organization, and revenue model differentiation - described in the analytical model of the previous section interact with each other and two organization level variables - integrated culture and venture differentiation - to lead to (mis) balance between financial and creative returns. In our research design and analysis, we followed the work of Fiss (2011), (2007), Ragin (2009), Schneider and Wagemann (2012), Schneider and Spieth (2013), and Schneider (2018).

4.3.1 QCA and its suitability for the study of business models and paradox management

Configurational perspective is based on the assumption that “cases under study [are] constellations of interconnected elements” (Misangyi et al. 2017, 256). QCA belongs to a family of comparative configurational methods (CCM) that allows for a systematical analysis of comparable cases to identify causally relevant structural conditions (variables) that lead to an identified outcome (Marx et al. 2013; Thiem, Baumgartner, and Bol 2015).

QCA is a set-theoretic method, employing a causes-to-effects approach to examine combinations of causal conditions (sets) instead of the more traditional search for linear causation (Mahoney and Goertz 2006). The method thus assists in answering questions that imply configurations, e.g. what conditions (X, Z, etc.) combine to cause an outcome (Y)? More precisely it looks at what conditions or combinations of conditions are necessary and/or sufficient for an outcome to occur. Necessary conditions are present whenever we observe an outcome. Sufficient conditions are conditions that display the presence of an outcome whenever the conditions are present. As all configurational methods, also QCA is based on three main assumptions: 1) relationships to outcomes are nonlinear and asymmetric; 2) variables that are causally related in one configuration are not necessarily related in others, implying complex causality; and 3) configurations can be equifinal (Fiss 2011, 2007).

The two following observations led to concluding that configurational approach is the most appropriate for our analytical framework: 1) The conceptualization of business models as a set of decision variables makes it a naturally configurational concept; 2) Both paradox theory and business model perspective oppose the contingency theory assumptions, i.e. “if-then” and “net-effects”, and instead look at the interaction between structures and practices and assume equifinality - idea that multiple configurations can have similar outcomes (Fiss et al. 2013; Nenonen and Storbacka 2010; Lewis and Smith 2014; Täuscher 2017).

Despite the apparent fit, not much configurational work exists in both areas. Even less so when it comes to linking the two streams. In paradox scholarship, the idea that organizations need both integrating and separating strategies is rather new, therefore not much research beyond theory building exists. In the case of business models, there has been a lack of methods that can empirically do justice to the complexity and configrutional nature of the concept. The lack of appropriate analytical tools has been a general problem of naturally configurational concepts. However, as argued by Fiss (2007) and Misangyi et al. (2017), the development of methods such as QCA has given rise to neoconfigurational perspective, allowing embracing causal complexity appropriately. These developments have paved the way to some recent applications of QCA in business model literature (Täuscher 2017; Kulins, Leonardy, and Weber 2016; Aversa, Furnari, and Haefliger 2015).

4.3.2 The process of fuzzy set QCA

QCA is case-oriented, as opposed to the variable-oriented methods (Marx et al. 2013). When applying QCA in organization studies, variables (referred to as conditions in QCA) are defined in terms of sets of organizational attributes. The choice of conditions can be both theoretical and empirical, namely, based on the knowledge of cases and the setting (Schneider and Spieth 2013). A set can be a single condition (e.g., client segmentation) or a combination of conditions (e.g., high creative AND business performance). Each case (firm’s survey response, in our case) is expressed in terms of its membership to the defined sets. The process of transforming gathered raw data about cases into membership scores is called calibration (Thiem and Dusa 2013). It prescribes the definition of three qualitative thresholds: full membership, the cross-over point, and full non-membership. The crossover point, contrary to most accepted measurement scales, establishes a difference in kind, not degree. It is the score that indicates the point of maximum ambiguity, when a firm has both a degree of membership and non-mebmerhsip of 0.5 in the given set (Jacobs 2017). For this study, we have chosen to carry out a fuzzy set QCA (fsQCA). In fsQCA cases are not only expressed in their full membership to the sets (1 is in, 0 is out), but also partial memberships can be assigned (partially in, partially out).

When the data is calibrated into sets, a truth table is computed. It is the main analytical device of QCA. It shows all the possible combinations of the defined conditions (for five conditions that would mean 32 possible combinations), also those that are not observed in the data. Each row of the table represents a unique configuration. To identify the configurations leading to the defined outcome, the truth table is futher minimized or reduced performing a systematic cross-case analysis based on Boolean algebra (Rihoux and Ragin 2009). In order to do so, the researcher has to: 1) set the tresholds of consisitency and frequency for rows to be allowed in the minimization, 2) specify the assumptions about directionality of the relationships between conditions and outcome, and about easy and difficult counterfactual analysis will be performend (Enhanced Standard Analysis), and 3) evaluate the model based on parameters of fit (Schneider and Wagemann 2012).

Consistency indicates the “degree to which a proposition about the sufficiency/necessity of a condition for an outcome is true.” (Thiem and Baumgartner, n.d.) It can have a value between 0 and 1. If the score is low, we cannot deem that a configuration is sufficient/neccessary, as it is not supported by empirical evidence. Frequency treshold refers to the number of empirical observations that display the specific configuration, in order for it to be inlcuded in the minimization.

In addition, three other parameters of fit assist in evaluating the model - coverage, proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) and relevance of neccessity (RoN). Coverage shows the percentage of cases observed for which the configuration is valid. Low coverge, as opposed to the case of consistency, does not indicate the irrelevance of the configuration, it is simply represented by few empirical instances. PRI shows the degree to which the specific configuration (or the whole solution) is not simultaneously sufficient for the presence of the outcome, as well as its absence. RoN is a measure of triviality that shows how close a conditions is to a constant (Schneider and Wagemann 2012; Thomann and Maggetti 2017). Table 4.11 shows an overview of the main possible issues in model evaluation and the ways we dealt with them.

In the minimization procedure, there are three search strategies that are applied each producing different solution types (Ragin 2009; Thiem and Baumgartner, n.d.; Schneider and Wagemann 2012). According to Ragin (2009), a thorough QCA produces all three of them in each analysis. The complex solution shows the configurations that are sufficient for the outcome without any counterfactual analysis, meaning, based only on the empirically observed instances, no logical reminders are included. The parsimonious solution on the contrary includes all the logical remainders, without evaluating their plausibility. This solution term is considered the most causally relevant, as it shows the largest solutions sets. The intermediate solution requires the researcher to make several evaluations: 1) in the unobserved configurations, are the conditions expected to contribute to the outcome in their presence or absence? (directional expectations based on theory), 2) are there any instances where the same rows are found to be sufficient for both the presence of the outcome and its absence?(easy counterfactuals)?, and 3) can / should conditions be removed in parsimonious solution based on substantial knowledge about them (difficult counterfactuals)?

In line with the currently accpeted standards of good practice in QCA (Ragin 2009; Fiss 2011; Thomann and Maggetti 2017), we report both core (⚫for presence and ⦻ for absence) and peripheral conditions (●for presence and ⦸ for absence). The peripheral conditions represent the ones present in the intermediate solutions, and the core conditions are the ones present in both the intermediate and parsimonious solutions. Blank spaces in the table indicate that in the given solution the condition is not causally relevant.

4.3.3 Research setting and data collection

Our analysis is based on 179 cases of Dutch creative service firms. The data for this studies was collected from two sources - interviews and a survey. The interview data allowed for a more in-depth understanding of the process of business model design, and paved the way to further develop the survey measures for the follow-up study. Table 4.1 shows the data sources. Measures are described in detail in the next section.

| Data source | Purpose / description |

|---|---|

| Interviews (n=16) | Development of the conceptual framework; Validating survey measures; Data for post-QCA analysis; |

| Expert interviews (n=4) | Developing and validating survey measures; Discussing the validity of interview findings |

| Survey responses (n=179) | Data for the QCA analysis; Data for the post-QCA analysis; |

| Secondary data | Additional data from websited, reports, field noted from events etc. |

The interview sample was targeted with diversity as the main criteria. In order to evaluate the sustainability of their performance, the firms were at least 5 years old and with a minimum of 5 full time employees. The first cases were gathered in the various subsectors of design and then further extended to other creative services, e.g. advertisement agencies, interactive and digital design consultancies. The semi-structured interviews with the founders or managers of the selected firms were conducted in 2015 and 2016, and lasted between 60 and 180 minutes. The interview guide was developed based on a prior literature review on business models, paradox management and the management characteristics of creative services firms. They were complemented with secondary data from websites, notes from various events where firms participated and reports. This data was used to develop measures for paradox management that could be used in survey research. It was distributed between June 2017 and March 2018. The survey was sent out to an initial sample of 125 members of Dutch Designers’ Association (n=25), and a follow up sample of a self-gathered data base of 6000 enterprises that according to the Dutch Chamber of Commerce have registered their activity as belonging to the creative service firms (n=154). Our final sample, after removing unfinished responses and thos that do not match the sampling criteria, consists of 179 cases. Table ?? in Appendix A shows the distribution of cases by sector and size of ther firm. Our firms consist of mostly micro firms (up to 10 employees) from the graphic design, advertisement, and architecture sectors.

4.3.4 Measures and calibration

All the measures for business-model-level conditions used in this study were single-item, measured on a 7-point Likert scale, asking the respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the statements about their business (1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree. The items are presented in Table 4.2. In order to calibrate the data into sets, we used direct calibration setting 4.01 as the first inclusion score in the set “differentiation”. This calibration strategy was used because Likert scales are naturally categorical, and the middle point (score 4) is expressed verbally as “neither agree, nor disagree”, which is an equivalent of the 0.5 neither member, nor non-member score in fuzzy sets. The non-membership would mean that the firms use an integration strategy with respect to the particular decision.

| Business-model-level condition | Survey measures |

|---|---|

| VPCH (Value proposition differentiation) | Some types of our services and products help reaching our financial and business goals, while others contribute to our creative goals. |

| SEGM (Approach to client segmentation) | Some client segments are commercial and bring in money, while others secure creative work, reputation and exposure. |

| RESDIF (Network differentiation) | We make a clear distinction between creative and business partners. |

| REVDIF (Diversification of payment systems) | Different revenue models and conditions are used for commercial projects and the projects we perceive as creative and/or challenging. |

In order to measure the two organization-level conditions we used multiple-item composite measures equally based on a 7-point Likert scale, asking the respondents to indicate the extent to which the statements are true about their business (Table 4.3). For the venture separation condition, we first asked if the company has any affiliate ventures, and if it did, weather their activity was focused on one of the performance goals more than the other. The maximum score of these two items was extracted for the calibration.

| Org-level condition | Survey measures |

|---|---|

| SPINDIF (Venture separation) | Composite measure (creative OR commercial affiliate venture Y/N). |

| The other venture(s) connected to our firm focus(es) on the more commercial and/or entrepreneurial work. | |

| The other venture(s) connected to our firm focus(es) on the more creative projects, as opposed to the commercial and entrepreneurial work. | |

| INTCULT (Venture separation) | Composite measure (the mean of both scores). |

| When it comes to our activities and processes, we always try to develop synergies and interactions between the creative and business-related aspects. | |

| When making decisions within our company, we seek synergies, integration, and compromises between our creative and commercial ambitions. |

Creative and business performance were measured using previously validated, but slightly adjusted multi-item scales from the study of Lander (2012) (the full item pool used for CFA can be found in ??). Creative performance scale consists of four items and the business performance scale of three items. The means of each performance dimension were calibrated using the direct method and 4.01 as the inclusion score. These were then transformed into a combined outcome set - BAL: high creative performance AND high business performance. In our analyses, we ran separate QCAs for the outcome and its absence.

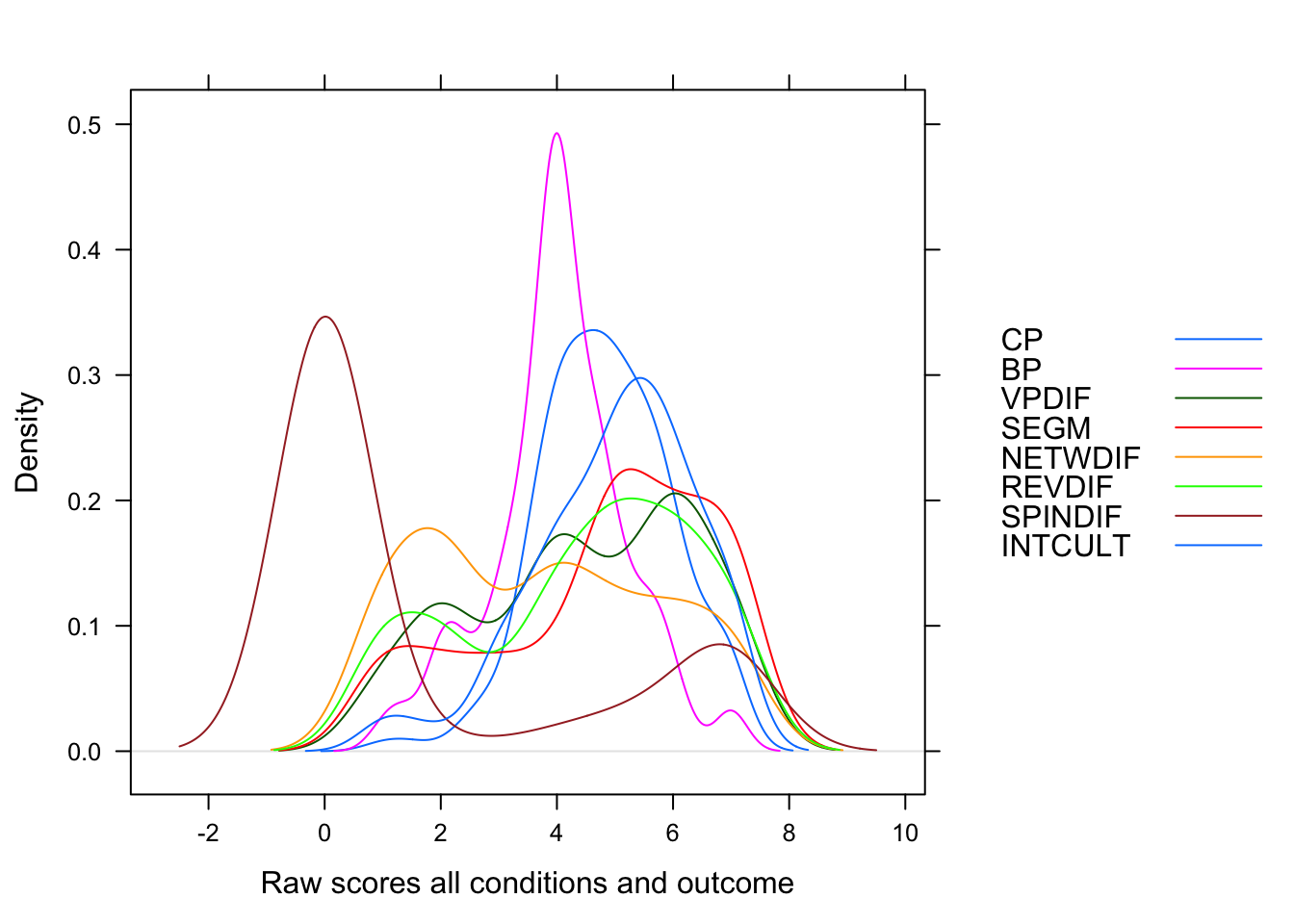

Table 4.4 shows correlations among our variables (further referred to as conditions, in line with QCA standards). As we can see, the differentiation strategies are significantly positively correlated with each other, while they are not correlated with any of the performance conditions. The only significant correlation in terms of performance and paradox management strategies is found between the creative performance and intergated organizational culture, which is in line with the theoretical expectations. These insights speak in favour of the application of a configurational approach to the analysis of our data. Appendix 4.8 presents more insights into the various descriptives of our raw and calibrated conditions.

| VPDIF | SEGM | NETWDIF | REVDIF | SPINDIF | INTCULT | CP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | |||||||

| SEGM | 0.34**** | ||||||

| NETWDIF | 0.28*** | 0.17* | |||||

| REVDIF | 0.38**** | 0.33**** | 0.34**** | ||||

| SPINDIF | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.08 | |||

| INTCULT | 0.15* | 0.16* | 0.25*** | 0.18* | 0.23** | ||

| CP | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.29**** | |

| BP | -0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.05 | 0.01 | -0.02 | 0.38**** |

Before reporting the analysis, it has to be noted that following the suggestions for best practices of QCA (Ragin 2009; Schneider and Wagemann 2012; Jacobs 2017), we also tried other direct calibration tresholds, as well as the TFR approach suggested by Duşa (2018). However, while the solutions did not change much in the different versions indicating the robustness of our results, the other calibrations led to a higher skewness of calibrated scores, hence lowering the consistency and PRI scores.

4.4 Results

Once the data was calibrated, we started our analysis with constructing a truth table (Table 4.12). Out of all the 64 configurations possible, there are 17 configurations of conditions not represented in our sample. This means they were either not observed or possibly do not even exist in the empirical world. There are no contradictory rows in our table, meaning that there are no cases where the same combination of conditions would show both balance and not-balance in both performance domains.

Since our literature review distinguished between conditions at two different levels - business model and organization - we first decided to try the two-step QCA (Schneider 2018) procedure for testing our hypotheses. Instead of treating all conditions as the same, the two-step QCA distinguishes between remote and proximate conditions. While the proximate conditions remain the main focus of the configurational analysis, the remote conditions are seen as contextual, i.e. outcome-enabling conditions. In our analysis it meant that we first tested for the neccessity of the integrated organizational culture and structural differentiation conditions (and of their disjunction), and the proceeded to testing the sufficiency of the (configurations of) differentiation strategies at the business model level for achieving high creative and high business performance simultaneously, including the found neccessary remote conditions, if any, in the analysis. On its own, integrated culture could be considered a neccessary set (Table 4.13) and a part of a neccessary superset INTCULT + SPINDIF <= BAL (Table 4.14). However, the Relevance of Neccessity scores of both are very low, suggesting that the sets are very large and thus possibly trivial. This was further confirmed when adding integrated culture as a condition in the sufficiency analysis, as would be appropriate according to the two-step QCA procedure. The analysis showed the absence of integrated culture as a individually sufficient condition, as well as gave many paths that included the absence of this condition in sufficient junctions, which logically contradicts the findings of the neccessity analysis. We therefore excluded the condition from the analysis, abandoned the two-step procedure, and proceeded with the regular QCA protocol, analyzing the neccessity and/or sufficiency of the remaining five conditions. This also meant rejecting Hypothesis 1.

In the two following sections, we present the results first for the solutions leading to outcome (both creative and business performances high) and then those leading to absence of it (firms that score low on one or both of the performance dimensions). In line with the theory, the directional expectations we formulated for deriving intermediate solutions were that for the analysis of BALANCE, all conditions contributed in their presence. For the absence of BALANCE analysis, accordingly, the conditions contributed in their absence.

4.4.1 Analysis 1: High creative, high business performance

As presented in Table 4.15 and Table 4.16, none of the conditions (in their presence, nor absence) were found as neccessary for the outcome to occur. We did find two neccessary disjunctions (sets that combine conditions through logicall OR) that passed the 0.9 consistency and 0.6 coverage tresholds - 1) absence of value propositon differentiation OR absence of revenue model differentiation OR presence of network differentiation (vpdif + revdif + NETWDIF), and 2) absence of client segmentation OR absence of revenue model differentiation OR presence of network differentiation (segm + revdif + NETWDIF). Yet, they should be interpreted with care, as the relevance of neccessity (RoN) for these supersets is relatively low (Schneider 2018). We can therefore simply expect that these conditions will be parts of sets that are sufficient for the outcome to occur.

| inclN | RoN | covN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vpdif+NETWDIF+revdif | 0.9290359 | 0.5013560 | 0.6154085 |

| segm+NETWDIF+revdif | 0.9014595 | 0.5121372 | 0.6078830 |

After the analysis of neccessity, we turned to the truth table minimization for testing sufficiency of (combinations of) our conditions for achieving high perfromance in both dimensions. The results presented in Table 4.6 show the two configurations of conditions (i.e. Solutions 1 ans 2) describing business-model-level paradox management stratgies, which, according to our analysis, are sufficient for creative firms to score high on both creative and business performance. The overall consistency of the model is 0.889. The model coverage is 0.401, indicating that 40 percent of the membership in the outcome set can be explained by the two configurations we found. While that is not a low score, it also indicates that the paradox management strategies do not account for all the aspects that would relate to performance in our setting (Fiss 2011). This is not a weird finding, seeing that business realities are more complex, and cannot be fully expressed in and explained by only five conditions.

| Conditions / Sol | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | ⦻ | ⦻ |

| SEGM | ⦻ | ⚫ |

| NETWDIF | ⦻ | |

| REVDIF | ⚫ | |

| SPIN | ⚫ | |

| Consistency | 0.827 | 0.928 |

| Raw coverage | 0.140 | 0.355 |

| Unique coverage | 0.046 | 0.261 |

| PRI | 0.407 | 0.497 |

| Nr. cases | 6 | 14 |

| Solution consistency | 0.889 | |

| Solution coverage | 0.401 | |

| Solution PRI | 0.486 | |

| Nr. Cases 1/0/C | 20 /157/0 |

In this analysis. both the intermediate and parsimonious solutions were the same, therefore all conditions in the table are core conditions.In Boolean terms the model can be expresses as follows:

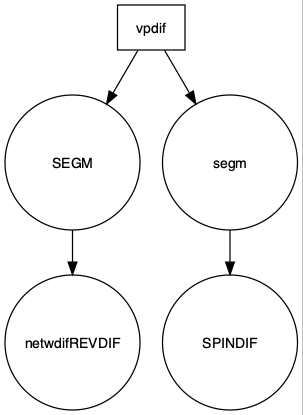

## [1] "vpdif*segm*SPINDIF + vpdif*SEGM*netwdif*REVDIF => BAL"The capital letters are used for conditions that contribute to the outcome in their presence, and miniscule in their absence. "*" designates the logical AND, while “+” refers to the logical OR. We can read this expression as 1) the absence of value proposition differentiation and clients segmentation in combination with the presence of a differentiated affiliate venture OR 2) the absence of value propositon differentiation and network differentiation in combination with the presence of differentiated client segments and revenue models are sufficient configurations for reaching high creative and business performance simultaneously. Figure 4.3 vizualizes the two solution paths.

The solutions of our model allow us to confirm Hypotheses 3a and Hypothesis 4. First, none of the solutions for achieving high creative and business performance show single solutions as sufficient and/or neccessary (H4). This provides evidence for the configuratinal nature of paradox management through business models. Second, both solutions consist of a combination of the presence of differention strategies, as well as their absence, instead of relying on only on differentiation or its absence (presumably - integration).

Third, at the more specific level of individual contributions of conditions, we can confirm Hypothesis 2b and reject Hypothesis 2a. According to the Solution 1, when firms have other ventures that take care of one of the two conflicting goals they are pursuing, at the focal firm level, value proprosition differentiation and client segmentation are causally relevant when absent. This means that if firms want to use structural separation they should abstain from differentiating their offering or segmenting clients. The other two domains - network and revenue models - in this case are not causally relevant. However, if firms combine differentiated revenue models and client segmentation, and do not differentiate at the value proposition and network level, it is (causally) irrelevant if they have other differenting ventures or not (H2a thus rejected).

Finally, since the Enhanced Standard Analaysis resulted in removing several very populated rows that were contradicting the sufficiency, as they were simultanesouly cosidered in the analysis of both presence and absence of the outcome, this model does not explain the success of all of the firms in our sample that were succesful.

Figure 4.3: Vizualization of sufficient configurations of conditions for BAL.

4.4.2 Analysis 2: Absence of a balanced performance.

As in the previous analysis, we first tested for neccessity relationships between our conditions and the absence of the outcome. Tables 4.17, 4.18 and 4.19 in Appendix D show all the results. Again, no individually neccessary conditions were found. As for superset-subset relationships, many of the disjunctions passed the consistency and coverage tresholds, but the RoN scored were not high enough to deem them actually neccessary for the absence of our outome.

The results in Table 4.7 present the six configurations (i.e., Solutions 3 to 8) leading to firms scoring low on one or both of the performance dimesions. The solution consistency is 0.713 and the coverage is 0.851, indicating that 85 percent of the cases that have low or no membership in the BALANCE set are explained by these configurations of conditions.

| Conditions / Sol. | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | ⦻ | ⚫ | ||||

| SEGM | ⦻ | ⚫ | ⚫ | |||

| NETWDIF | ⚫ | ⦻ | ⚫ | |||

| REVDIF | ⦻ | ⚫ | ⦸ | |||

| SPINDIF | ⦻ | ⦻ | ⚫ | ⦸ | ||

| Consistency | 0.869 | 0.779 | 0.829 | 0.859 | 0.833 | 0.751 |

| Raw coverage | 0.379 | 0.442 | 0.461 | 0.394 | 0.184 | 0.502 |

| Unique coverage | 0.042 | 0.030 | 0.084 | 0.028 | 0.050 | 0.033 |

| PRI | 0.210 | 0.152 | 0.367 | 0.295 | 0.193 | 0.523 |

| Nr. cases | 21 | 50 | 30 | 47 | 7 | 77 |

| Solution consistency | 0.713 | |||||

| Solution coverage | 0.851 | |||||

| Solution PRI | 0.430 | |||||

| Nr. Cases 1/0/C | 126/ | 51/ | 0 |

In this case, the intermediate and parsimonious solutions differed, we hence report both core and peripheral conditions. In Boolean terms, the intermediate solutions can be expressed as follows:

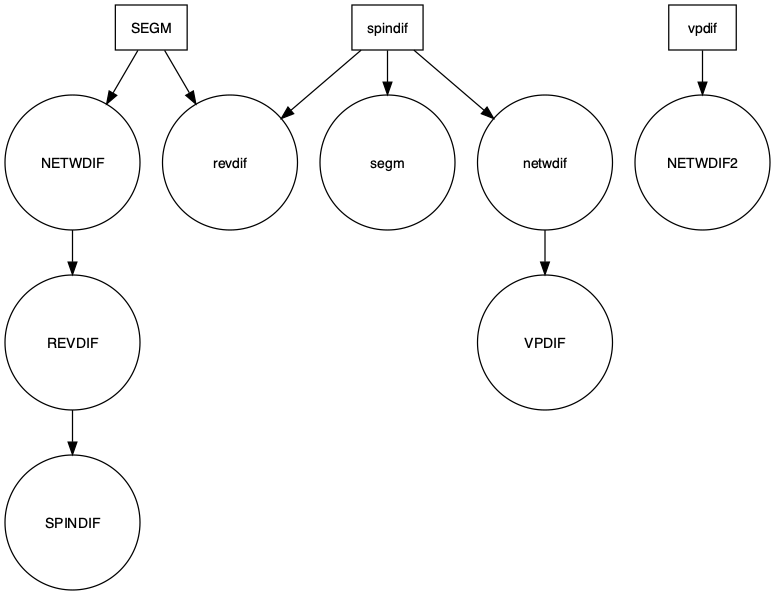

## [1] "vpdif*NETWDIF + segm*spindif + SEGM*revdif + VPDIF*netwdif*spindif + + NETWDIF*REVDIF*SPINDIF + revdif*spindif => bal"All in all, the first apparent finding is that there are more ways to “fail” than to succeed. The six solutions paths vizualized in Figure 4.4 show a more complex picture than in the previous analysis.

Second, we also observe that the results on failed performance confirm the expecations of Hypothesis 2b (with the exception of Solution 6). In the Solutions 4 and 8 the absence of separated ventures would require the presence of another differentiation strategy to be implemented, yet when combined with either the absence fo segemented client groups, or differentiated revenue models, it is a sufficient path to failure. Solution 6, however, gives contrary evidence to this hypothesis. While expected to lead to a balance, the absence of differentiated venture(s) in combination with a differentiated value proposition and an integrated network, actually lead to the absence of a balanced performance. We hence conclude that for success, it matters not only if the intergation and differentiation decisions are combined, but also to which of the business modelling domains they are applied to.

Third, the solutions of our model allow us to only partially accept Hypothesis 3b, which stated that configurations relying only on differentiation (or absence of it, assumed to be integration) will lead to balance. According to Solutions 8, 7, and 4, which are also among the most represented solutions, that is true. Firms that use only differentiation or integration fail. However, we also see that there are sufficient configurations explaining the lack of creative and/ or business performance that consist of both differentiation and the absence of it (Solutions 3, 5, and 6). We elaborate on the meaning of these findings more in the discussion setting.

Figure 4.4: Vizualization of sufficient configurations of conditions for ~BAL.

4.5 Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to understand how different differentiation strategies at the business model level can combine in order to perform well in two conflicting domains simultaneously. In particular, we examined the creative service firm setting to uncover which configurations of differentiation decisions with respect to value propositions, clients, network composition, and revenue models 1) contribute to a high performance in both conflicting strategic goals, 2) lead to a misbalance towards either creative or commercial performance, or both. Connecting to ambidexterity and paradox management literature, the underlying question was - when pursuing conflicting performance goals, how much can a firm differentiate? The short answer would be - in a balanced way. Based on our comparative configurational analysis, we were able to find two pathways to a balance in both creative and business performances, and six pathways that lead to a low performance on one or both dimensions. Table 4.8 presents an overview of the results with respect to the hypotheses formulated in the first part of this article. Our findings allow making three more general conclusions, based on which we further expand the discussion to more specific configurational aspects.

| Hypothesis | Status |

|---|---|

| H1:Whenever venture separation is present, integrated organizational culture should also be present achieving both high creative and commercial performance. | Rejected |

| H2a:The absence of paradoxical venture separation will require other differentiating paradox management strategies to be implemented at the business model of the focal firm (INUS condition) for the firms to be succesful at both performance dimensions. | Rejected |

| H2b: The presence of paradoxical venture separation will require other differentiating paradox management strategies at the business model to contribute to the success in their absence (INUS condition). | Partially accepted |

| H3a: Balanced performance patterns will be result from business model designs that rely on a mix of both presence and absence of differentiation strategies. | Accepted |

| H3b: Unbalanced performance patterns will result from business model designs that only rely on presence or absence of differentiation strategies. | Partially accepted |

| H4: Portfolio diversification, client segmentation, network differentiation, and dual revenue models are INUS conditions for achieving high creative and commercial performance simultaneously. | Accepted |

Our first finding relates to what Fiss (2018) discussed with respect to the applicability of the Anna Karenina principle to organizational outcomes. According to the principle, there are many ways to fail and only few ways to succeed. Our results confirm this proposition, as we find more complexity in the analysis of absence of balanced performance, than its presence. Moreover, in the context of paradoxical settings, failure has at least three forms (low creative performance, low business performance, both low), while success - only one (both performance dimensions high); and success is intentional, but failure is not. The solutions for success, though not always easy to implement, are fewer and more straight-forward than those for failure. This adds an extra challenge for interpreting the results adequatly (Fiss 2018).

Our second main finding relates to the role of the higher level strategies of paradoxical resolution discussed widely in the ambidexterity literature, namely, structural separation and integrated culture. According to our analysis, and contrary to much of the literature, none of the variables individually, nor jointly were able to explain the success or failure of managing conflicting goals. On the one hand, the model that included integrated organizational culture was “difficult”, for the set proved to be trivial in pluralistic settings. On the other hand, the paradoxical venture separation proved to be an INUS condition, meaning that it only causally contributed to success in combination with other non-differentiating decision. Moreover, based on Solution 2, it is not even always important if firms use structural separation or not. We can thus conclude that models that only look at organizational level strategies cannot fully explain success in paradoxical settings.

Third, and most importantly, our results highlight the configurational and assymetric nature of both business modelling and paradox management. In none of the solutions for both success and failure, a single condition was sufficient for the outcome; they all consist of junctions of conditions. Moreover, while our findings partially confirm the expectations in paradox management, namely, that firms cannot rely only on a single strategy, the paths and interactions are more complex than hypothesized - the causal contributions of conditions changed together with other conditions they were combined with. We can thus conclude that differentiating, as suggested in the literature, can be good for firms in paradoxical settings, but the strategy has to be applied with caution, as they way it is implemented, and with what they are combined matters (Smith 2014; Fairhurst et al. 2016). This article provides first insights informing the combining of different differentiation (and implicitly integration) strategies. A closer examination of our results allow to do some more theory building on that.

4.5.1 Towards a configurational theory of differentiation for paradoxical goals through business models.

The patterns across both analysis allow making some conclusions on the similarities, differences and complementarities between the different decision-making strategies and domains they are applied to. More precisely, the results allow us to divide the decision domains examined in two groups: - The “what we offer” decisions in the business model: venturing, value proposition design, or client selection. - The “how we offer” decisions in the business model: network composition and revenue model choice.

According to the solutions found, firms can only differentiate at one of the domains in each group, otherwise they fail. Solution 1 shows that the differentiation at the venture level is combined with absence of differentiation in the other “what” domains. Solution 2 shows a combination of differentiation in one “what” domain and absence in the other two, and one “how” domain, and absence in the other. Solutions for failure (except solution 7) show that if there is no differentiation in one of the two groups, firms do not succeed. Also if too much differentiation is applied (Solution 7), it also does not work. Thes findings are in line with the literature discussing the implementation of multi-sided business models, which can get too difficult if designed as too complex and separatly running systems (Parmentier and Gandia 2017). Our findings provide more insights on what one can and should not combine when designing business models for paradoxical goals.

4.6 Acknowledgment

This study is a part of the project ‘The battle of the souls: Cultural and business orientations of creative firms and their effects on business models, growth and internationalisation’(407-12-002), funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). The authors would like to thank Bart Cambr??, Michael Baumgartner, and Jan van den ende for their helpful suggestions on earlier versions of the paper.

4.7 Appendix A: Sample description

4.8 Appendix B: Measures and calibration

| Items (original pool) | Business performance | Creative performance |

|---|---|---|

| Gross profits per partner. (BP_1) | 0.729 | |

| Competitive hourly fee. (BP_2) | ||

| Gross margin on provided services. (BP_3) | 0.730 | |

| Competitive cost structure. (BP_4) | ||

| Overhead percentage. (BP_5) | ||

| Retention of the largest clients. (BP_6) | ||

| Implementing new business models. (BP_7) | ||

| Retention of clients. (BP_8) | ||

| Attracting new clients. (BP_9) | ||

| Growth in profits. (BP_10) | 0.810 | |

| Growth in staff. (BP_11) | ||

| Efficient firm organization. (BP_12) | ||

| Producing highly innovative work. (CP_1) | 0.749 | |

| Working on projects that challenge the boundaries of the field. (CP_2) | 0.787 | |

| Attracting the best creative professionals. (CP_3) | ||

| Reputation on the labor market. (CP_4) | ||

| Reputation among peers. (CP_5) | ||

| Receiving good critic’s reviews for its work. (CP_6) | ||

| Receiving industry awards for its work. (CP_7) | ||

| Delivering work that is relevant for the society. (CP_8) | ||

| Working on projects that match the firm’s creative and professional aspirations. (CP_9) | 0.734 | |

| Creating the desired impact with its work. (CP_10) | 0.679 | |

| Keeping the employees challenged and satisfied. (CP_11) | ||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.798 | 0.824 |

| AVE | 0.577 | 0.552 |

| Chi-Square | 0.006 | |

| RMSEA | 0.084 | |

| SRMR | 0.045 | |

| CFI | 0.964 |

| var | min | max | mean | sd | skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | 1 | 7 | 4.469274 | 1.864182 | -0.3323053 |

| SEGM | 1 | 7 | 4.782123 | 1.911677 | -0.6540864 |

| NETWDIF | 1 | 7 | 3.720670 | 2.005657 | 0.1758287 |

| REVDIF | 1 | 7 | 4.413408 | 1.950811 | -0.4280053 |

| SPINDIF | 0 | 7 | 1.636872 | 2.769615 | 1.1967321 |

| INTCULT | 1 | 7 | 4.997207 | 1.383589 | -0.7108549 |

| CP | 1 | 7 | 4.840782 | 1.107526 | -0.2069791 |

| BP | 1 | 7 | 4.039218 | 1.154125 | -0.1088203 |

Figure 4.5: Distribution of raw scores all conditions and outcomes.

| Perc. 0 | Perc.1 | |

|---|---|---|

| VPDIF.Freq | 0.4916201 | 0.5083799 |

| SEGM.Freq | 0.3296089 | 0.6703911 |

| NETWDIF.Freq | 0.6368715 | 0.3631285 |

| REVDIF.Freq | 0.4413408 | 0.5586592 |

| SPINDIF.Freq | 0.7709497 | 0.2290503 |

| INTCULT.Freq | 0.2793296 | 0.7206704 |

| CP.Freq | 0.2793296 | 0.7206704 |

| BP.Freq | 0.5921788 | 0.4078212 |

| BAL.Freq | 0.6648045 | 0.3351955 |

| NOBP.Freq | 0.6145251 | 0.3854749 |

| NOCP.Freq | 0.9273743 | 0.0726257 |

| BOTHLOW.Freq | 0.7932961 | 0.2067039 |

4.9 Appendix C: Model evaluation

| Issue | Description | Solution strategy | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement errors | Sensitivity to changes in raw consistency levels | Raw consistency | Use of three different raw consistency thresholds |

| Robustness test | |||

| Plausibility & tenability | Limited diversity & contradictions can trigger inferences that are implausible and/or contradictory | Enhanced Standard Analysis | Intermediate solution based on directional expectations and exclusion of contradictory rows and untenable assumptions |

| Causal relevance | Only parsimonious solution removes causally irrelevant conditions from solution term | Comparative presentation of parsimonious & intermediate solution | Parsimonious solution is causally interpretable and less sensitive to errors |

| Skewness | Skewed distributions can produce simultaneous subset relations, exacerbate limited diversity, and strongly distort parameters of fit | Skewness statistics | % of cases with membership > 0.5 in sets in reported. Skewness is problematic if the vast majority (> 85%) of the cases cluster in only one of the four possible intersecting areas of the XY plots with two digitals |

| Accuracy | Degree to which observations correspond to set relation | Consistency | Necessity: ??? 0.9 |

| Sufficiency: ??? 0.75 | |||

| Explanatory power | Empirical relevance of model | Coverage | Necessity: ??? 0.6 |

| RoN: ??? 0.8 | |||

| Sufficiency: Low coverage indicates low explanatory power |

4.10 Appendix D: Analyses

| VPDIF | SEGM | NETWDIF | REVDIF | SPINDIF | INTCULT | OUT | cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 81 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 98 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 29,88,167,173 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 154 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 93,178 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 41,124 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 52 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 48,163 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 149,169 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 50,122,147 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 37,158 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 84 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 131,153 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 42 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 66 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 61 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 23 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 83,126 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 56,129 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 18,19,40,73,91,99,103,128,140,170 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 102,161,171 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15,116 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7,10,76 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 27,65,78,104,112,117 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 11,70,109 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 69,96,111,123,150 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 67,168 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 22,25,44,144,155 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1,5,58,82,87,92,105,136,148,157 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 68 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 45,47,63,95,145 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 17,32,89,113,165,179 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 49,60,127,177 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 35,71,106,130,174 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 31,51,175 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8,13,21,26,55,62,85,115,159 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6,57,151 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 79,110,120 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 36 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9,20,38,46,53,77,132,133,138,143,152,164 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 86,141,172 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30,43,64,94,101,118,137 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 24,34,54,59,107,108,114,134,139,142,156,162,166 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2,3,12,28,33,39,72,74,75,80,90,97,119,121,160,176 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14,16,125,135,146 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ? | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ? | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? |

| Cons.Nec | Cov.Nec | RoN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPINDIF | 0.279 | 0.568 | 0.883 |

| INTCULT | 0.899 | 0.628 | 0.554 |

| inclN | RoN | covN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPINDIF+INTCULT | 0.9074356 | 0.5050243 | 0.6072057 |

| Cons.Nec | Cov.Nec | RoN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | 0.761 | 0.625 | 0.658 |

| SEGM | 0.803 | 0.600 | 0.585 |

| NETWDIF | 0.639 | 0.673 | 0.786 |

| REVDIF | 0.760 | 0.626 | 0.659 |

| SPINDIF | 0.279 | 0.568 | 0.883 |

| Cons.Nec | Cov.Nec | RoN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| not VPDIF | 0.620 | 0.707 | 0.826 |

| not SEGM | 0.531 | 0.704 | 0.857 |

| not NETWDIF | 0.724 | 0.633 | 0.693 |

| not REVDIF | 0.613 | 0.698 | 0.820 |

| not SPINDIF | 0.809 | 0.505 | 0.383 |

| Cons.Nec | Cov.Nec | RoN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | 0.765 | 0.688 | 0.698 |

| SEGM | 0.796 | 0.650 | 0.617 |

| NETWDIF | 0.616 | 0.710 | 0.806 |

| REVDIF | 0.757 | 0.682 | 0.694 |

| SPINDIF | 0.276 | 0.612 | 0.893 |

| Cons.Nec | Cov.Nec | RoN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPDIF | 0.765 | 0.688 | 0.698 |

| SEGM | 0.796 | 0.650 | 0.617 |

| NETWDIF | 0.616 | 0.710 | 0.806 |

| REVDIF | 0.757 | 0.682 | 0.694 |

| SPINDIF | 0.276 | 0.612 | 0.893 |

| inclN | RoN | covN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vpdif+SEGM | 0.9114042 | 0.4578478 | 0.6262697 |

| VPDIF+netwdif | 0.9326466 | 0.4439410 | 0.6307326 |

| vpdif+REVDIF | 0.9165169 | 0.5147943 | 0.6542840 |

| VPDIF+revdif | 0.9185385 | 0.5139814 | 0.6548621 |

| SEGM+netwdif | 0.9336735 | 0.4027958 | 0.6144657 |

| SEGM+revdif | 0.9232876 | 0.4506366 | 0.6289941 |

| SEGM+REVDIF | 0.9002588 | 0.4776924 | 0.6295260 |

| netwdif+REVDIF | 0.9484769 | 0.4286521 | 0.6321196 |

| VPDIF+segm+NETWDIF | 0.9405725 | 0.4590069 | 0.6409283 |

| VPDIF+SEGM+NETWDIF | 0.9147948 | 0.4292424 | 0.6158399 |

| VPDIF+segm+REVDIF | 0.9407757 | 0.4234499 | 0.6262505 |

| VPDIF+segm+SPINDIF | 0.9122920 | 0.4877812 | 0.6398932 |

| VPDIF+SEGM+SPINDIF | 0.9079173 | 0.4175866 | 0.6076179 |

| segm+NETWDIF+REVDIF | 0.9261969 | 0.4644295 | 0.6363175 |

| segm+REVDIF+SPINDIF | 0.9129123 | 0.4702616 | 0.6324096 |

| vpdif+segm+NETWDIF+revdif | 0.9038100 | 0.4811378 | 0.6327996 |

| vpdif+NETWDIF+revdif+SPINDIF | 0.9145274 | 0.4432026 | 0.6215497 |

| segm+NETWDIF+revdif+SPINDIF | 0.9053288 | 0.4657955 | 0.6267475 |

| vpdif+segm+netwdif+revdif+SPINDIF | 0.9113721 | 0.4491759 | 0.6225323 |

Bibliography

Andriopoulos, Constantine, and Marianne W. Lewis. 2009. “Exploitation-Exploration Tensions and Organizational Ambidexterity: Managing Paradoxes of Innovation.” Organization Science 20 (4): 696–717.

Bednarek, Rebecca, Gary Burke, Paula Jarzabkowski, and Michael Smets. 2016. “Dynamic Client Portfolios as Sources of Ambidexterity: Exploration and Exploitation Within and Across Client Relationships.” Long Range Planning 49 (3). Elsevier: 324–41.

Yunus, Muhammad, Bertrand Moingeon, and Laurence Lehmann-Ortega. 2010. “Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience.” Long Range Planning 43 (2). Elsevier: 308–25.

Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur. 2010. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. John Wiley & Sons.